ඩුයිස්බර්ග් හි එලිසබෙත් සිමර්මන්-මොඩ්ලර්ගේ අවමංගල්යය: “අසාමාන්ය ලෙස ධෛර්ය සම්පන්න පෞරුෂයක්”

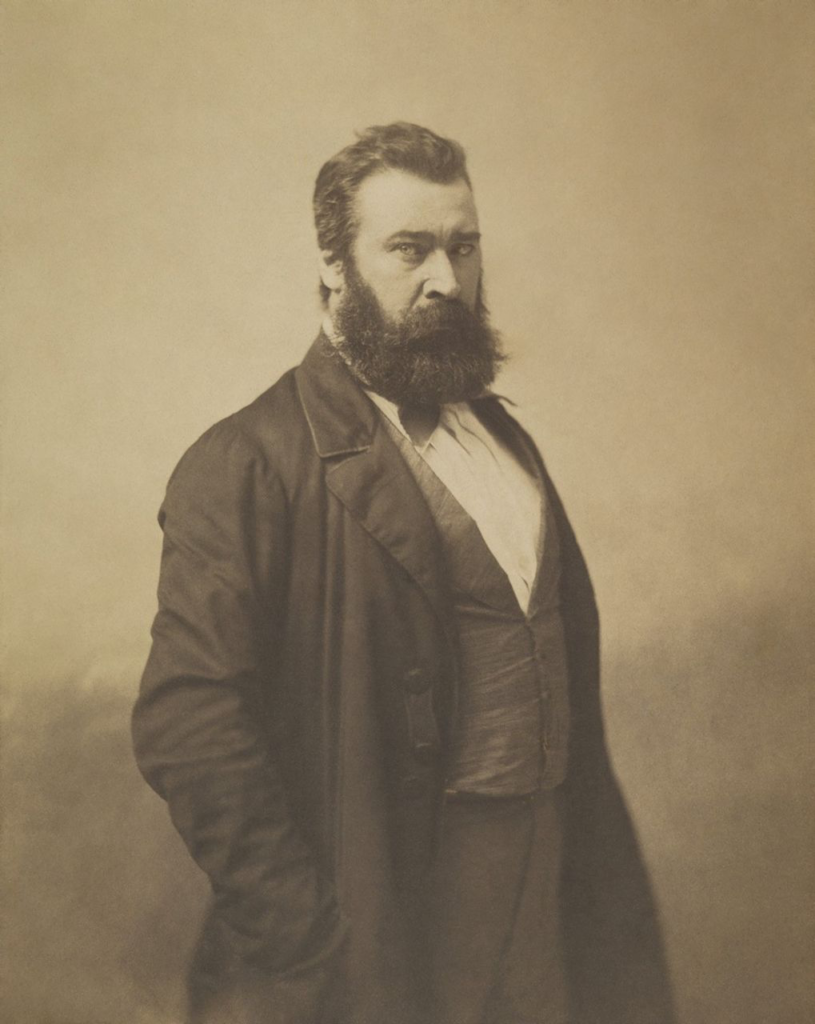

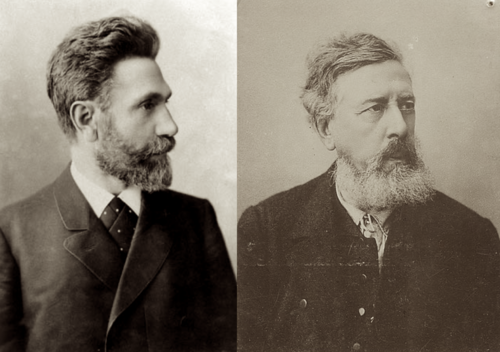

සමාජවාදී සමානතා පක්ෂයේ (ජර්මනිය) සම්භාවනීය සභාපති උල්රිච් රිපට්

මෙහි පලවන්නේ ලෝක සමාජවාදී වෙබ් අඩවියේ (ලෝසවෙඅ) 2025 දෙසැම්බර් 23 දින ‘The funeral of Elisabeth Zimmermann-Modler in Duisburg: “An extraordinarily courageous personality”’ යන හිසින් පලවූ ලිපියේ සිංහල පරිවර්තනය යි.

“එලී අසාමාන්ය ලෙස ධෛර්ය සම්පන්න පෞරුෂයක් වූවාය. ඇය ඉතා නිරවුල් බවකින් සහ සංගතභාවයකින් ඇගේ ජීවන මාවත තරණය කළාය.”

මෙය ප්රකාශ කරන ලද්දේ එලිසබෙත් සිමර්මන්-මොඩ්ලර්ගේ අවමංගල්ය උත්සවයේදී ජර්මනියේ සමාජවාදී සමානතා පක්ෂයේ (Sozialistische Gleichheitspartei – SGP) ගරු සභාපති උල්රිච් රිපර්ට් විසිනි. “එලි” ලෙස කවුරුත් දන්නා ඇය වසර 50 ක් SGP හි සාමාජිකාවක් වූවාය. ඛේදජනක අනතුරක ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස ඇය නොවැම්බර් 28 වන දින වයස අවුරුදු 69 දී මිය ගියාය.

ශීතඍතුවේ මලින වූ දිනයක් වූ සිකුරාදා, එලිසබෙත් සිමර්මන්-මොඩ්ලර්ට අවසන් ගෞරව දැක්වීම සඳහා ශෝක වන්නන් 50 ක් පමණ රුහ්රෝර්ට් සුසාන භූමියට රැස් වූහ. වයලීන වාදක එලා රොට්ෂ් යොහාන් සෙබස්තියන් බාක් විසින් රචිත “එයාර්” (Air) වාදනය කළාය. පැමිණ සිටි අය අතර, වසර ගණනාවක් තිස්සේ එලීව හඳුනන SGP සාමාජිකයින්ට අමතරව, සීමන්ස් හි වැඩ සගයන්, තයිසන්කෘප් හි වානේ කම්කරුවෙකු ලෙස සේවය කළ ඇගේ සැමියා වන පීටර්ගේ සගයන් කිහිප දෙනෙකු මෙන්ම අසල්වැසියන් සහ මිතුරන් ද වූහ. දෙමළ සහෝදරයෙකු වන තාස්, එලී තමා සහ ශ්රී ලංකාවේ අනෙකුත් සරණාගතයින් ඇයගේ නිවසට ගෙන ගිය ආකාරය, ට්රොට්ස්කිවාදයේ මූලධර්ම පිළිබඳව ඔවුන්ට අධ්යාපනය ලබා දුන් ආකාරය සහ ජීවිතයේ සෑම අවස්ථාවකදීම තමා මිතුරියක් බව ඔප්පු කළ ආකාරය සොහොන් බිමේදී සිහිපත් කළේය. “ඇය අපේ පවුල විය,” තාස් පැවසීය.

උල්රිච් රිපර්ට්ගේ කතාව එලිසබෙත් සිමර්මන්-මොඩ්ලර්ගේ ජීවිතයට උපහාරයක් විය. පැමිණ සිටි වානේ කම්කරුවන් ඇතුළු බොහෝ දෙනෙක් පසුව පැවසුවේ රිපර්ට් එලීගේ චරිතය හරියටම ග්රහණය කරගත් බවයි. කතාව පහත පරිදි වේ:

ආදරණීය පීටර්, එලීගේ ආදරණීය ඥාතීන්, ආදරණීය සහෝදරවරුනි සහ මිතුරනි,

එලීගේ හදිසි හා ඛේදජනක මරණයෙන් අපි තවමත් දැඩි ලෙස පීඩාවට පත්ව සිටිමු. නොවැම්බර් 28 වන දින උදෑසන සිදු වූයේ කුමක්ද යන්න හෝ ඇගේ මහල් නිවාසයේ මෙම විනාශකාරී ගින්න ඇති වූයේ කෙසේද යන්න අපි තවමත් නොදනිමු. අපි දැඩි ලෙස කම්පනයට පත්ව සිටිමු.

වසර තුනකට පෙර ඇයට ඇති වූ ආඝාතය සහ එතැන් සිට ඇයට ගැනීමට සිදු වූ ඖෂධ ඇයට දැඩි ලෙස බලපෑ බව අපි දැන සිටියෙමු. අද මෙහි රැස්ව සිටි බොහෝ දෙනෙක් ඇගේ අසනීපයේ ප්රතිවිපාක දුටුවෝය. එය සැබවින්ම ඛේදජනකයි. අපි එලීගේ වෛද්ය ප්රතිකාර වැඩිදියුණු කිරීමේ ක්රියාවලියක යෙදී සිටියා, එහෙත් දැන් මරණය අපව අභිබවා ගියා.

ඇගේ අසනීප තත්ත්වය නොතකා, එලීට සෑම දෙයකටම සහභාගී වීමට අවශ්ය විය. අපෙන් බොහෝ දෙනෙක් දින කිහිපයකට පෙරත් ඇයව බර්ලිනයේ පැවති උත්සවයකදී මුණගැසී ඇය සමඟ කතා කර සාකච්ඡා කළා.

එලී අසාමාන්ය ලෙස ධෛර්ය සම්පන්න පෞරුෂයක් වූවාය. ඇය ඉතා නිරවුල් බවකින් සහ සංගතභාවයකින් ඇගේ ජීවන මාවත තරණය කළාය.

එලී ජීවිතයේ හිරු රැසින් දිදුලන පැත්තේ ඉපදුනේ නැහැ. ඇය ලෝකයට එන විට යුද්ධය සහ නාසි අපරාධ අවසන් වී ගෙවී තිබුණේ වසර එකොළහක් පමණයි. ඇගේ ළමා කාලය සහ තරුණ කාලය, ජර්මානු සමාජයට සහ පවුල්වලටම ගැඹුරින් විනිවිද ගිය නාසීන්ගේ අපරාධ සහ යුද්ධවලින් ඉතිරි වූ තුවාල සහ කැළැල් මගින් සලකුණු වුනා.

ඇගේ මව දැන් චෙක් ජනරජය ලෙස හඳුන්වන උතුරු බොහීමියාවෙන් පිටුවහල් කර තිබුණි; එලී ඉපදෙන විට ඇයට වයස අවුරුදු 17 ක් පමණි. ඇය තනි මාපියෙකු ද, ගුරුවරියකද වූ අතර රැකියාවක යෙදීමට සිදු විය. එලී හදා වඩා ගැනීම සඳහා පවුලකට භාර දුන් අතර ඇගේ මුල් ළමා කාලය එහි ගත කළාය. වයස අවුරුදු දොළහේදී, එලීට සංකීර්ණ කොඳු ඇට පෙළේ සැත්කමකට භාජනය වී ප්ලාස්ටර් ඇඳක මාස ගණනාවක් වැතිර සිටීමට සිදු විය. ඇගේ ජීවිත කාලය පුරාම පිට කොන්දේ ගැටළු ඇය සමඟ පැවතුනි.

නමුත් එලී මේ සියලු දුෂ්කරතා වලට අභියෝග කළාය. ඇය ජීවිතය ඉතා ධනාත්මකව තහවුරු කළ පුද්ගලයෙකි.

මම මුලින්ම එලීව මුණගැහිලා අවුරුදු 50කටත් වැඩියි. ඒ 1975 මැයි මාසේ මුල. එවිට ඇයට වයස අවුරුදු 19ක් වූ ඇතර ද්විතීක අධ්යාපන උපාධිය සඳහා සූදානම් වෙමින් සිටියා. මේ පළමු හමුවෙහිදී ම අපි තීව්ර සාකච්ඡා පැවැත්වූ බවත්, සමීප සහයෝගීතාවයක් ආරම්භ වූ බවත් මට මතකයි.

නාසි ත්රස්තයේ අපරාධ තවමත් ඉතා සජීවීව පැවති පරම්පරාවකට එලී අයත් වූවාය. ඉතා දියුණු සංස්කෘතියක් සහ ශක්තිමත් කම්කරු ව්යාපාරයක් සහිත නූතන රටක ම්ලේච්ඡත්වයට නැවත කඩාවැටීමක් සිදුවූයේ කෙසේද යන ප්රශ්නය ඇය සහ ඒ කාලයේ අප සියල්ලන්ම අලලා ගත්තා.

තරුණ වියේදී පවා, එලී නාසිවාදයේ විරුද්ධවාදීන්ගේ ලේඛන කියවා තිබූ අතර, වතිකානුව සහ නාසීන් අතර සහයෝගීතාවය පිළිබඳව සාකච්ඡා කළ වූ රොල්ෆ් හොචුත්ගේ ද ඩෙපියුටි නාට්යය (The Deputy) ද ඒ අතර විය. ඇයගේ සංගත භාවයට අනුකූලව ඇය, ඉන් ඉක්බිතිව පල්ලියෙන් ඉවත් වූවාය.

එකල බොහෝ දෙනෙක් ෆැසිස්ට්වාදයට හේතු කාරනා, මහජන මනෝවිද්යාව සහ ජර්මානු ජනතාව පරිහරණය වීමට ගොදුරු වීමේ ප්රවණතාව අනුව පැහැදිලි කළහ. එලී එවැනි සරල හා නොගැඹුරු පිළිතුරු වලින් සෑහීමකට පත් නොවීය. ඇයට අවශ්ය වූයේ දේවල්වල මූලයට යාමටයි.

ෆැසිස්ට්වාදය සහ ධනවාදය අතර සම්බන්ධතාවය ගැන එලී සාකච්ඡා කළාය. හිට්ලර්ට මහා කර්මාන්ත මුදල් මගින් සපයා ඇති බවත් ඔහු බලයට ගෙන එන ලද්දේ ඔවුන් බවත් ඇය දැන සිටියාය.

පසුව, ෆැසිස්ට් පක්ෂ නැවතත් ගොඩනඟමින් බලයට ගෙන ඒමට හේතුව තේරුම් ගැනීමට නම්, ධනවාදය සහ ෆැසිස්ට්වාදය අතර මෙම සම්බන්ධතාවය මෙතරම් වැදගත් වන්නේ මන්දැයි අවධාරණය කරමින් ඇය ලිපි කිහිපයක් ලිවීය.

නමුත් පසුව තවත් ප්රශ්නයක් මතු විය: 1933 දී කම්කරු පන්තිය නාසීන්ගේ ජයග්රහණය නතර කර ම්ලේච්ඡත්වයට පල්ලම් බැසීම වළක්වා නොගත්තේ මන්ද?

මෙයට පිළිතුරු දීම සඳහා, ස්ටැලින්වාදයට එරෙහිව සමාජවාදයේ ඉදිරිදර්ශනය ආරක්ෂා කළ ලියොන් ට්රොට්ස්කිගේ ලේඛන පිළිබඳ දැඩි අධ්යයනයකට එලී සහභාගී විය. ට්රොට්ස්කි පෙන්වා දී තිබුණේ හිට්ලර්ට බලයට පැමිණිය හැකි වූයේ ස්ටාලින් ඔහුගේ “සමාජ ෆැසිස්ට්වාදයේ” ප්රතිපත්තිය මඟින් කම්කරු පන්තිය බෙදීම හා දුර්වල කිරීම නිසා පමණක් බවයි.

නිගමනය පැහැදිලිය: යුද්ධය සහ ෆැසිස්ට්වාදය වැළැක්විය හැකි එකම සමාජ බලවේගය කම්කරු පන්තිය පමණි. නමුත් මේ සඳහා ශක්තිමත් විප්ලවවාදී පක්ෂයක් අවශ්ය වේ.

එලී මෙම නිගමනයට එළඹුණු අතර, පළමුව, සමාජවාදී සහ, දෙවනුව, ජාත්යන්තර නව කම්කරු පක්ෂයක් ගොඩනැගීම සඳහා උද්යෝගිමත් සටන්කරුවෙකු බවට පත්විය

ආදරණීය මිත්රවරුනි, මෑත දිනවල මම මෙහි එලීගේ සොහොන අසලදී කුමක් කිව යුතුදැයි සිතමින් සිටියදී, එලී විසින්ම කුමක් කියයිදැයි මම මගෙන්ම විමසුවෙමි. හදිසියේම මට ඇගේ පැහැදිලි කටහඬ ඉතා ප්රත්යක්ෂව ඇසුණි–ව්එලීට හයියෙන්, පැහැදිලිව, ස්වාභාවික ආකාරයෙන්ම හා ඉතා ඒත්තු ගැන්වෙන ලෙසටම කතා කළ හැකි විය–ඇය මෙසේ පැවසුවාය: “ඇයි ඔබ සරලවම සත්යය නොකියන්නේ? මම ඉතා දේශපාලනික ජීවිතයක් ගත කළෙමි. ඒ වගේම මම ඒ ගැන ආඩම්බර වෙමි!”

එලීගේ ජීවිතය තුළ ඉතා දර්ශීය (typical) හා සිත් කාවදින දෙයක් තිබේ. මම විශ්වාස කරන්නේ එය සංගතභාවය (consistency) ලෙස හඳුන්වන බවයි. ඇය කාල් මාක්ස්ගේ ආප්තයට අනුව ජීවත් වූවාය: “යමෙක්ට තමන් එළඹෙන නිගමනවලට බිය නොවී සිතීම සදහා ධෛර්යය තිබිය යුතුය–ඉන්පසු ඒවා මත ක්රියා කළ යුතුය.”

එලී මෙම ආප්තයට අනුව ජීවත් වූවාය. ඇය නිවැරදි යැයි හඳුනාගත් දේ–රැඩිකල් ලෙස සහ සියලු ප්රතිවිපාක සමඟ–ඇය ක්රියාවට නැංවූවා ය. යුද්ධයට සහ ෆැසිස්ට්වාදයට එරෙහිව විරෝධතා දැක්වූ ඇගේ පරම්පරාවේ එකම තැනැත්තා ඇය පමණක් නොවීය, එනමුත් නිවැරදි නිගමනවලට එළඹුණු සහ සම්මුති විරහිතව ඒවා තදින් අල්ලා ගත් ඉතා ස්වල්ප දෙනා අතර ඇයද වූවාය.

සාමවාදීන්ගෙන් හිස්ටීරික මිලිටරිවාදීන් බවට පරිවර්තනය වූ හරිත පිල්මාරු කාරයන් ඇය පිළිකුල් කළාය. වමට කතා කර දකුණට ක්රියා කරන වාම පක්ෂයේ (Left Party) මුසාවන්ට එරෙහිව ඇය සටන් කළාය.

එලීගේ ජීවිතයේ විශේෂයෙන් කැපී පෙනෙන දේවල් දෙකක් තිබේ.

පළමුව, ඇය කම්කරු පන්තිය දැන සිටි අතර එය තේරුම් ගත්තාය. ඇය එහි කොටසක් වූවාය. ඇය Siemens හි වසර 35 ක් සේවය කළ අතර එහි සාප්පු භාරකරුවෙකු (shop steward) ලෙස කටයුතු කළාය. වසර හතළිස් දෙකකට පෙර, ඇයට ඇගේ අනාගත සැමියා වන පීටර් මොඩ්ලර් මුණගැසුණි. ඔහු වානේ කම්කරුවෙකු ලෙස සේවා මුර වැඩ කළ අතර Thyssenkrupp හි සාප්පු භාරකරුවෙකු විය. ඔහු ඇගේ දේශපාලන කටයුතුවලට දැඩි ලෙස සහාය දුන්නේය.

නමුත් කම්කරුවන් සමඟ කතා කරන විට පවා, ධනපතියන්ගේ කෲරත්වය, දොට්ට දැමීම් සහ සේවා කොන්දේසි නිරන්තරයෙන් පිරිහීම ගැන පැමිණිලි කිරීම පමණක් ප්රමාණවත් නොවන බව එලී අවධාරණය කළාය. රජයේ සහ පාලක ප්රභූවේ වගකීම් විරහිතභාවය ගැන කෝපයට පත්වීම පමණක් ප්රමාණවත් නොවේ. තමන්ගේම වගකීම හඳුනාගෙන භාර ගැනීම අවශ්ය වේ.

“කම්කරුවන්ගේ විමුක්තිය කම්කරුවන්ගේම කාර්යය විය යුතුය” යන මාක්ස්ගේ ප්රකාශය එලී දැන සිටි අතර ඇය එය ඉතා බැරෑරුම් ලෙස සැලකුවාය.

එලීගේ දෙවන කැපී පෙනෙන ලක්ෂණය වූයේ ඇගේ ජාත්යන්තරවාදයයි.

එය ඇයට ලොව පුරා මිතුරන් සිටීම පමණක් නොවේ. ජාත්යන්තරවාදය දේශපාලන වැඩසටහනක් ලෙස ඇය තේරුම් ගත්තාය. වෘත්තීය සමිති සහ ධනේශ්වර පක්ෂවල ජාතිකවාදයට එරෙහිව ඇය සටන් කළාය. කම්කරුවන්ට මාතෘ භූමියක් නොමැති බවත්, ඔවුන් ලෝක නිෂ්පාදන ක්රියාවලියේදී ගෝලීය වශයෙන් අන්තර් සම්බන්ධිත බවත් ඇය දැන සිටියාය. සෑම රටකම කම්කරුවන් එකම හෝ සමාන ගැටලුවලට මුහුණ දෙන බවත්, ධනවාදයට එරෙහි අරගලය සාර්ථක විය හැක්කේ එය ජාත්යන්තරව සිදු කළහොත් පමණක් බවත් ඇය බොහෝ විට අවධාරණය කළාය.

බොහෝ රැස්වීම්වලදී, සරණාගතභාවය සඳහා ඇති අයිතිය ක්රමානුකූලව අහෝසි කිරීමට එරෙහිව සහ විදේශිකයන් ඉලක්ක කරගත් උද්ඝෝෂණවලට එරෙහිව එලී සටන් කළාය. සංක්රමණිකයන් සහ සරණාගතයින් ජාත්යන්තර කම්කරු පන්තියේ වැදගත් කොටසක් බවත්, විදේශිකයන්ට එරෙහි සියලු ප්රහාර අධිෂ්ඨානශීලීව ප්රතික්ෂේප කළහොත් පමණක් කම්කරුවන්ට තමන්ගේම අයිතිවාසිකම් ආරක්ෂා කර ගත හැකි බවත් ඇය අවධාරණය කළාය.

කම්කරු ව්යාපාරයේ සෑම අවස්ථාවාදී ධාරාවක්ම ආරම්භ වන්නේ ජාතිකවාදයට අනුවර්තනය වීමෙන් බව එලී දැන සිටි අතර, වසර හතළිහකට පෙර අපගේ සහෝදරවරුන් අතර එවැනි ආරවුලක් ඇති වූ විට, ඇය වහාම සහ පැකිලීමකින් තොරව ජාත්යන්තරවාදීන්ගේ පැත්ත ගත්තාය.

ලෝක පක්ෂයක් ලෙස අපගේ පක්ෂය ගැන එලී ඉතා ආඩම්බර වූ අතර බොහෝ ජාත්යන්තර රැස්වීම් සහ සම්මන්ත්රණවලට සහභාගී විය.

දශක ගණනාවක් තිස්සේ ඇය අප සමාජවාදී සමානතා පක්ෂයේ විධායක කමිටුවේ සාමාජිකාවක් වූවාය; ඇය බොහෝ මැතිවරණවලදී අපේක්ෂිකාවක් ලෙස ඉදිරිපත් වූ අතර ගුවන් විදුලියේ සහ රූපවාහිනියේ අපගේ වැඩසටහන ඉදිරියට ගෙන ගියාය.

මෙම දැඩි දේශපාලන කටයුතු මධ්යයේ වුවද, ඇය සංස්කෘතික දේ සඳහා කාලය සොයා ගත්තාය. ඇය සාහිත්යය, සිනමාව, ඔපෙරා සහ ප්රසංගවලට ප්රිය කළාය.

එලීගේ මරණයේ ඛේදවාචකය හරියටම පවතින්නේ ඇය ඇගේ මුළු වැඩිහිටි ජීවිතය පුරාම සටන් කළ දේශපාලන අදහස් සහ ඉදිරිදර්ශන එතරම් විශාල අදාළත්වයක් සහ වැදගත්කමක් ලබා ගන්නා මොහොතේම ඇයව ජීවිතයෙන් ඉරා වෙන් කර දැමීම තුළය.

ආදරණීය එලී: ඔබ තවදුරටත් අප සමඟ නොමැති වීම ගැන අපි අතිශයින් කණගාටු වෙමු. අපට ඔබ නැති අඩුව දැනේ. නමුත් ඔබ ඔබේ ජීවිතය කැප කළ අරගලය අපි දිගටම අරගෙන යන්නෙමු.

කම්කරු පන්තියේ විමුක්තිය සඳහා සටන්කරුවෙකු ලෙස ඔබ සැමවිටම අපගේ මතකයේ ජීවමාන වනු ඇත. අපි එය පොරොන්දු වෙමු.

වැඩිදුර කියවන්න: Elisabeth Zimmermann-Modler 1956–2025: Trotskyist and fighter for the working class